Strangles is a highly contagious upper respiratory bacterial disease of horses that is commonly found in Australia. It is caused by the bacteria Streptococcus equi subspecies equi). Horses, ponies and donkeys of all types and ages can be affected, but young and geriatric horses typically develop more severe signs with it sometimes becoming fatal in these animals. It is often observed in spring and summer due to higher amounts of horse movement and mingling during these months.

Signs of strangles

A horse suffering from strangles will typically have a temperature (above 38.5°C), depression, and often a loss of appetite, and this will occur up to 14 days, but most usually between 3 and 10 days after initial infection with the bacteria . They will also develop a thick, yellow mucous draining from both nostrils. Particularly, hot and painful abscesses may develop on the sides of the head and throat, within the retropharyngeal lymph nodes, which may burst and discharge pus. The horse may experience difficulty eating or extending his head, due to the discomfort in its throat.

Strangles can sometimes produce more subtle signs in a healthy adult horse, who may only display a slight short-term increase in temperature, a brief loss of appetite and a clear nasal discharge.

In severe cases however, the abscesses in the throat region can cause difficulties with eating and breathing if they put pressure on the airway. Horses usually recover fully after natural rupture of the abscesses although up to 10% of horses can remain chronic carriers of the disease. Up to 75% of horses develop strong natural immunity to reinfection for a period of time (possibly years).

Rare complications include bastard [metastatic] strangles, where abscesses form elsewhere in the body, and the immune system disorder purpura haemorrhagica which often leads to death in the affected horse.

How is strangles spread?

The bacteria is spread by direct horse-to-horse contact or from humans moving between horses. Additionally, tack, feed buckets, water troughs, fences, floats and the pasture can all be infective. The bacteria can only live in the environment for a short period of time, but in ideal conditions this can be for several weeks, so complete decontamination of a facility or stable is often required.

Importantly, horses do not have to come into contact with the purulent discharge to be infected. This is because shedding of the bacteria from recently infected horses begins 2 to 3 days after onset of fever and before lymph node enlargement and nasal discharge occurs. Additionally, there can be carrier horses that appear outwardly healthy but harbour the bacteria in their upper respiratory tract for months and even years after infection. Also, most horses shed the bacteria for 2 to 3 weeks (or longer) after the onset of fever and after clinical recovery. Therefore, seemingly healthy horses may be shedding strangles into the environment and infecting other horses.

How is strangles treated?

The bacteria that causes strangles can be killed by certain antibiotics, including Penicillin. It can be challenging to decide when antibiotics are appropriate in cases of strangles and it is important to consult with a veterinarian about their use. Usually it is recommended to only treat with antibiotics in more complicated or severe cases, as antibiotics can delay resolution of abscesses and increase risk of the infection spreading throughout the horse’s body (‘bastard strangles’).

From a practical perspective, early detection of infection begins by taking your horses’ body temperatures at least twice daily. Horses that are inappetant may require anti-inflammatories to encourage them to feel better and eat. Caution must be taken that animals receiving anti-inflammatories are also drinking and not dehydrated, or gut and kidney damage can result.

Recommended treatments include application of heat (hot water bottles or towels) to the swollen

glands to encourage abscesses to burst or to grow to a size and maturity that allows them to be safely and successfully lanced open. Once open, the abscess cavities should be flushed with dilute povidone iodine solutions and allowed to heal naturally.

Diagnosis & Prevention

Diagnosis is made by a veterinarian based on history and clinical signs along with laboratory confirmation via Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and sometimes with culture of the bacteria. Samples collected for this are usually nasal swabs.

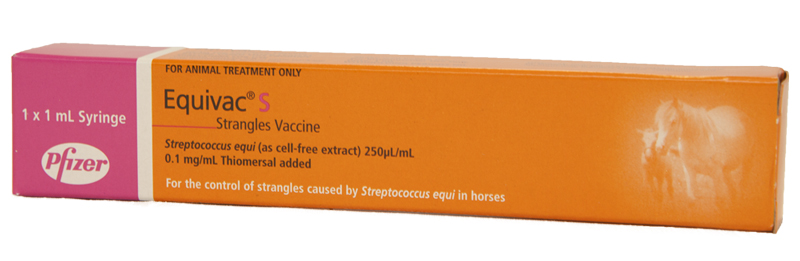

Vaccination to reduce the risk of horses contracting the disease is an effective means of prevention. It is recommended that horses receive an initial 3 injections 2 weeks apart with yearly boosters. It is important to note however, vaccination will not 100% prevent a horse from contracting the disease, but importantly, will drastically reduce the symptoms and duration of illness if contracted.

If the disease is confirmed on your property, to reduce spread of infection it is important to isolate any horse suffering with the condition and undertake good hygiene precautions and suitable biosecurity to prevent transferring the infection to others. In the event of an outbreak, emergency vaccinating at-risk horses is recommended to reduce the severity of symptoms and length of disease.

At Southwest Veterinary Group we aim to supply vaccines at the most competitive prices in the district so come in and see us at our new home in Park street to ensure your horse is up to date with all its vaccines for the spring season.